Donate to watch

The Scripture of Nature (1851-1890)

S1 E1 / 1h 55m

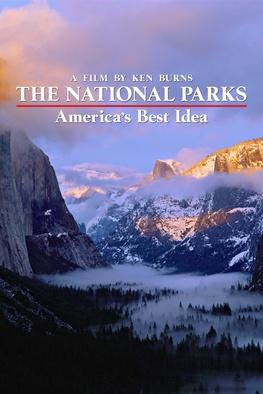

In 1851, word spreads across the country of a beautiful area of California’s Yosemite Valley, attracting visitors who wish to exploit the land’s scenery for commercial gain and those who wish to keep it pristine. Among the latter is a Scottish-born wanderer named John Muir, for whom protecting the land becomes a spiritual calling.